Recognised as a narrative painter, Sydney-based Tanya Chaitow’s current exhibition is informed by an exploration of the work of the Old Masters, particularly the European paintings from the 18th and 19th centuries where the upper classes are portrayed in bucolic landscapes. Her interest in this era stemmed from a time when she was working directly from the paintings of Francesco Goya in the Prado Museum, Madrid.

‘Art is a cultural reflection of a civilisation,’ Chaitow imparts. ‘The history of art is an infinite source of inspiration and I am attracted to the way art describes the zeitgeist of its time. My present body of work questions the traditional canons of beauty and identity and the way women have been objectified. I am enjoying turning classical portraiture upside down and disturbing the veneers of gentility. Historical genre paintings are re-imagined and the female forms have been transposed from their place of origin into chimerical landscapes. Through decontextualization and the masking the faces, I build a new narrative – an alternative, fantastic portrayal of women who in turn are part autobiographical, part historical, part hybrid dream-creatures. The imagery speaks to both the past and present.’

A love for animals and nature and the interconnectedness of all living things is evident in Chaitow’s paintings. ‘As in previous bodies of works, the relationships between humans, their environment and their animal neighbours are integral to my sense of being,’ Chaitow continues. ‘Anthropomorphised characters populate the paintings. They contain personal traits that represent parts of my own psyche.’ She tells of how growing up in South Africa’s post-colonial apartheid era engendered an awareness and respect for animals. ‘In Africa animals have long been feared, revered and employed as shamanistic links between this world and the spiritual realm. Simultaneously, the hunting of exotic animals as trophies epitomise the patriarchal domination of nature and natives by colonial powers. I hope to highlight such exploitation and the ongoing need for action on the preservation of the natural environment.’

The imagery in the painting, The Whisper of a Tiger’s Tale (after Sir Joshua Reynolds), reflects Chaitow’s environmental and cultural concerns. Simulating Reynolds’ 18th century portraiture style, a female figure stands in the foreground beside a tree. Chaitow’s woman, however, has the head of a tiger and a tail protruding from elaborately formal attire. Her countenance projects the strength, fearlessness, determination and independence traditionally attributed to the tiger.

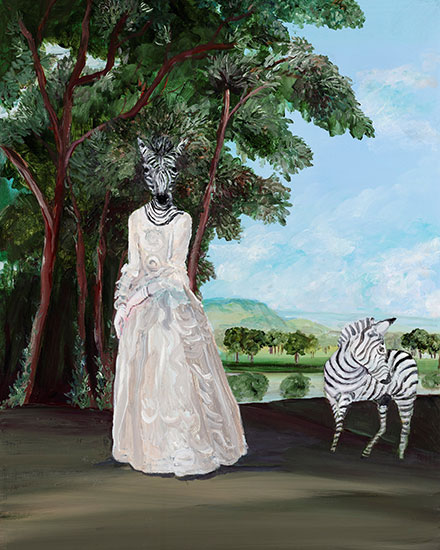

The Space Between Me and You (after Arthur Devis) is another intriguing work. Devis was a Georgian-era artist known for his portraits that were called ‘conversation pieces’. They were termed such because of their depiction of genial tête-à-têtes in an idealised outdoor setting. Although the landscape is akin, Chaitow’s painting has a different ambience. Appearing to have emerged from a grove of trees, a young woman in the fashionable, fine silk dress of the day, is mute under her zebra headpiece. Directly facing the viewer, she accompanied by a zebra who has turned away, its attention elsewhere. Chaitow comments that the woman is ‘both hidden and free’ due to her concealed visage.

Derived from a specific work by French genre artist, Louis Leopold-Boilly, Chaitow describes the painting Does the Life We Lead Belong to Us (after Louis Boilly) as speaking of her own youth and immigration to a new country. In it a young girl, straw hat in hand, stands in a wooded clearing contemplating her changed surrounds as if awoken from a dream. ‘Relocating the kangaroo to the European landscapes challenges our sense of reality and history and reminds us of our colonial past,’ she relays. ‘The small bridge is a formal device linking the background and foreground, simultaneously acting as a metaphor in the journey to the subconscious.’

The only work in the exhibition depicted within a quiet domestic interior is We Are Reading the Story of Our Lives (after Joseph Karl Stieler). Its title is from a quote by poet Mark Strand that pertains to interior and

external realities. Here the seated females are portrayed as cut-out dolls sharing an oversized voluminous dress. One is vigilant, the other self-absorbed. Behind them the wallpaper motif appears to continue over their gown as if they too are part of the wall. An environmental melding is suggested. The tiny, two-leafed pot plant in hand and basket of flowers on the floor link the internal to the hazy natural world outside. The oversized topiary form outside the window is a reference to the penchant of the 18th century elite to clip natural foliage into artificial shapes. From the leafage, a pair of eyes observe the women. ‘In this picture we question who the observer is,’ says Chaitow.

‘Although there is a strong narrative content in the works, I’m actually a very intuitive painter, even down to the pictures I choose to paint from,’ discloses Chaitow. ‘I allow the act of painting to prompt a direction and am reluctant to spell out all the symbolism. It is more important that a work hovers on a poetic plane where meaning is sensed rather than understood. In my paintings I hope to conjure up a mystical otherworldliness where we are caught between reverie and wakefulness; the rational and the quixotic.’

Speaking of the exhibition’s title, The Whisper of a Tiger’s Tale, Chaitow imparts, ‘These paintings are part self-portrait, part dreamscape and partly my personal mythology. It is a whisper of how I tell my own story, with my own voice, about my own life experience.’

JACQUELINE HOUGHTON

Receive e-mail updates on our exhibitions, events and more

Subscribe Now